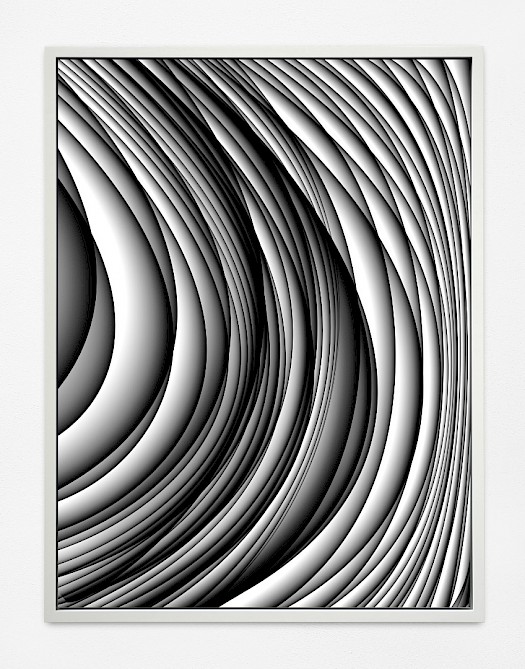

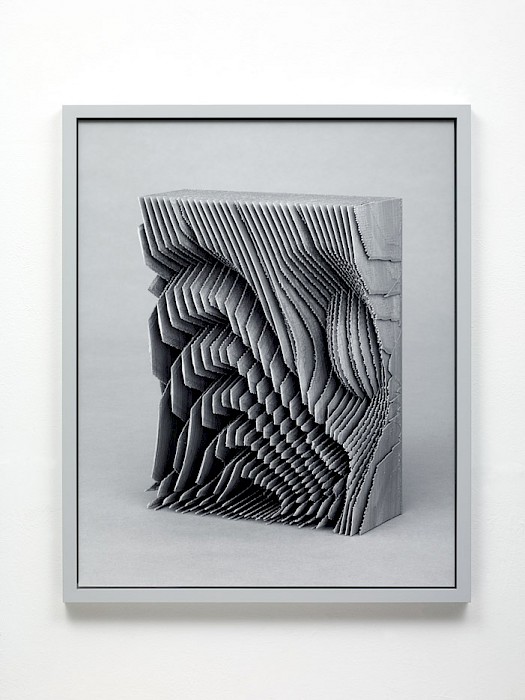

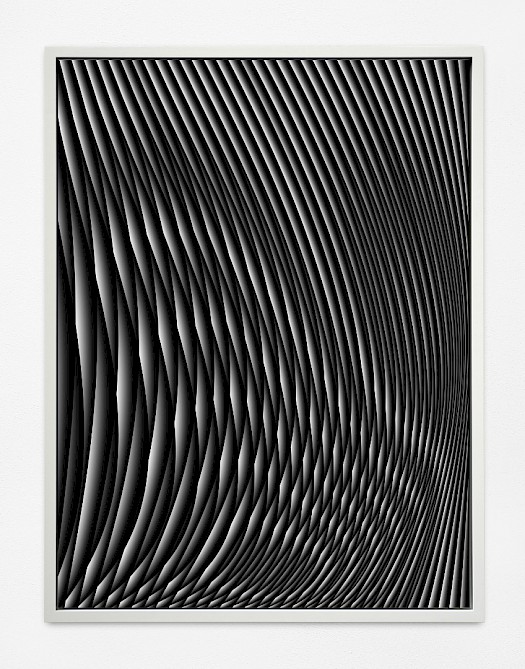

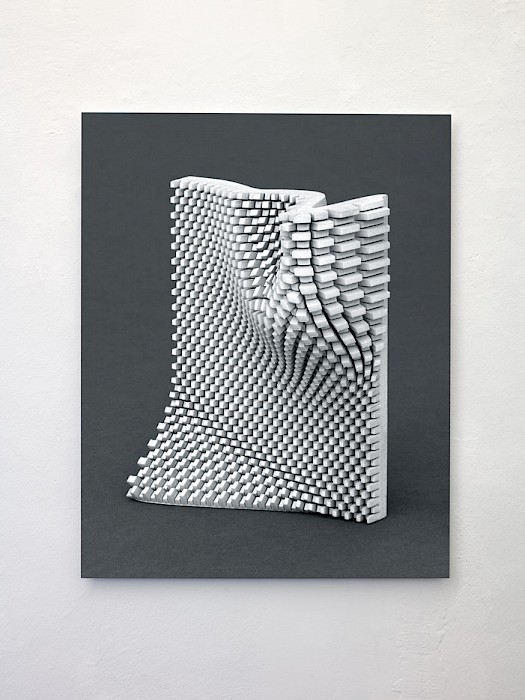

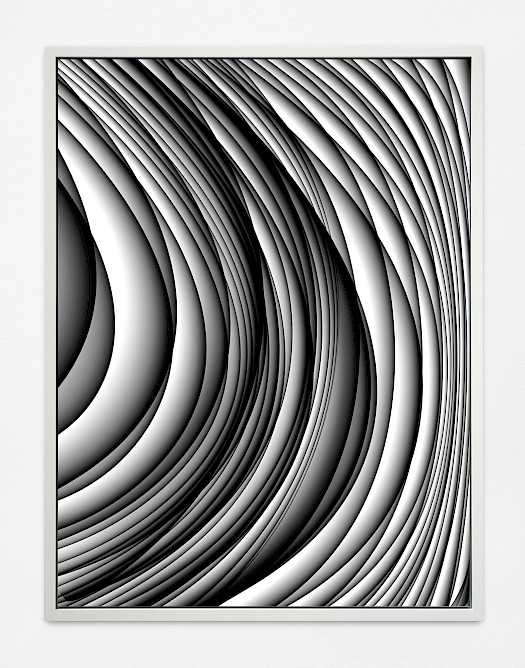

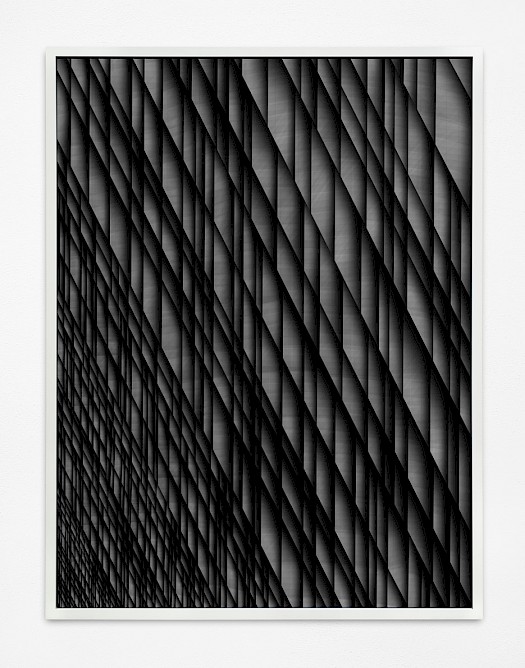

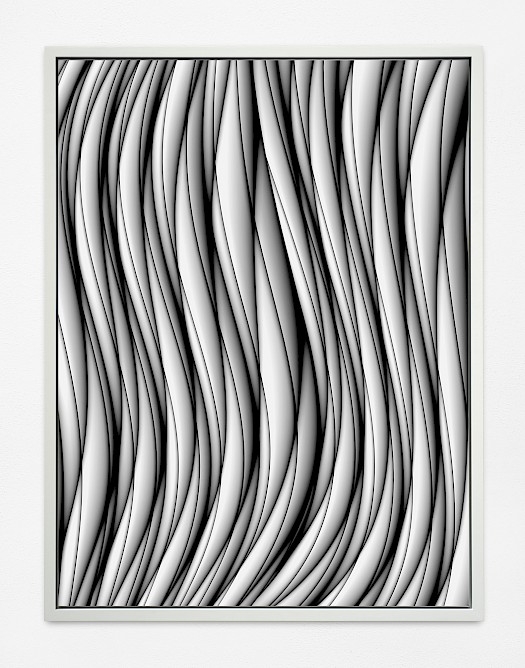

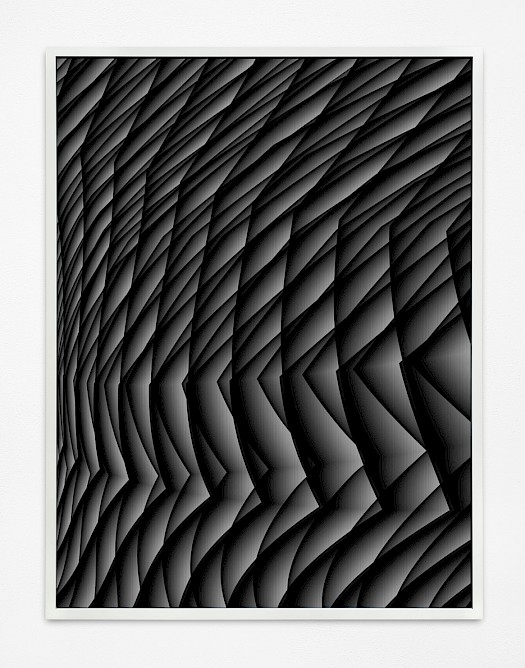

english: „MURRAY; DONDIE; REBECCA - trust in those who supposedly know”, working process, 5-2024

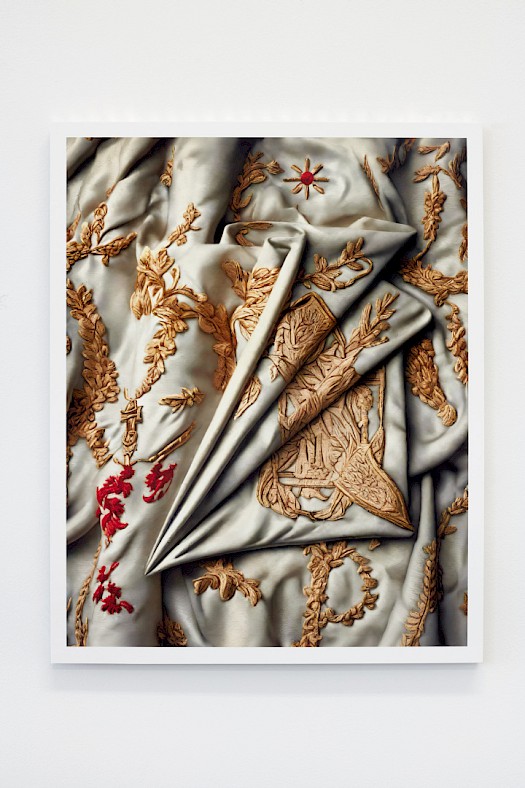

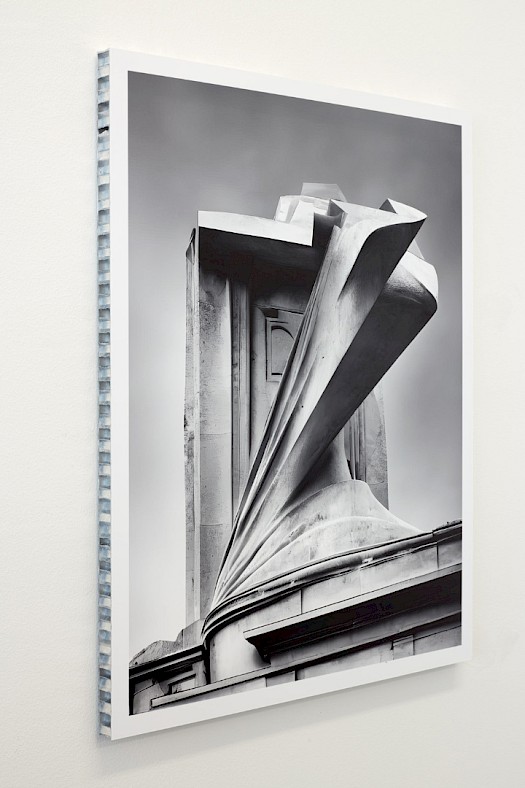

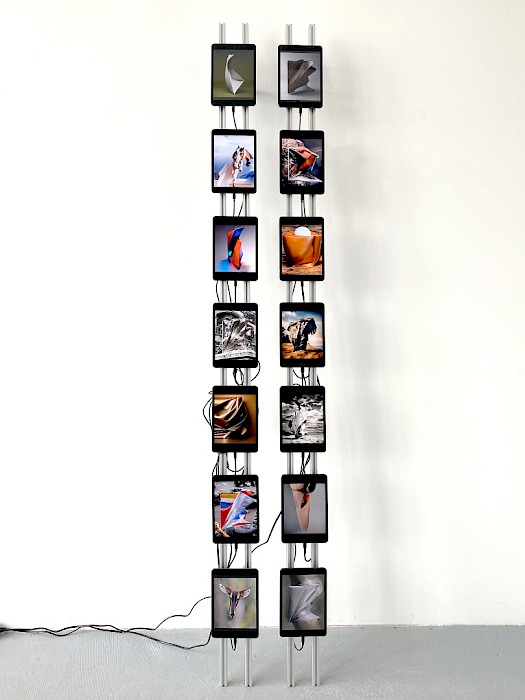

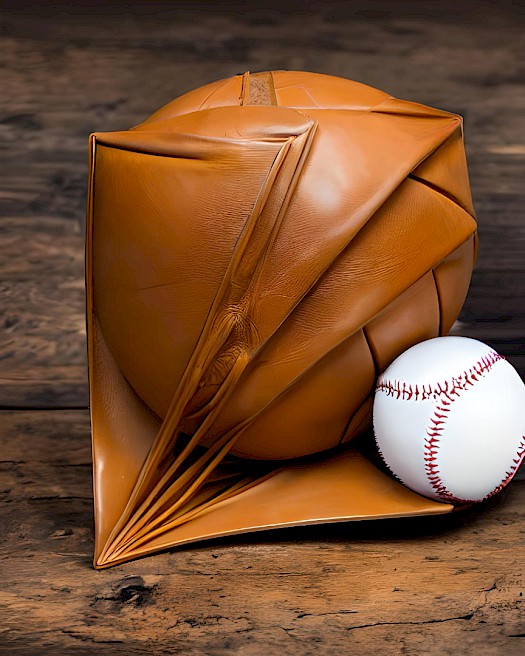

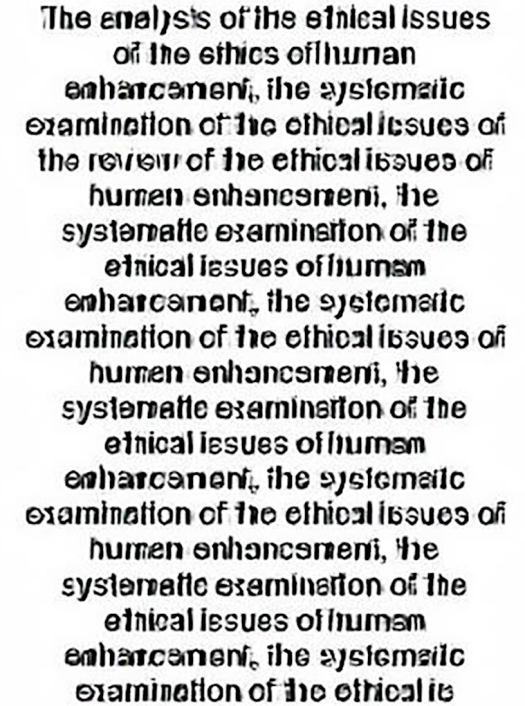

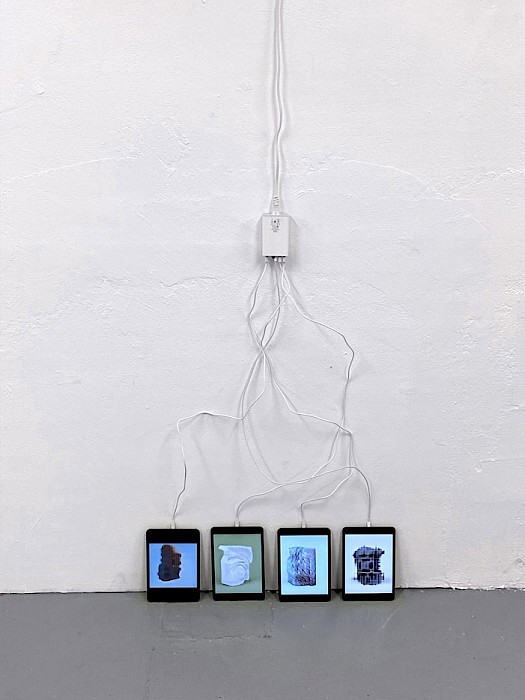

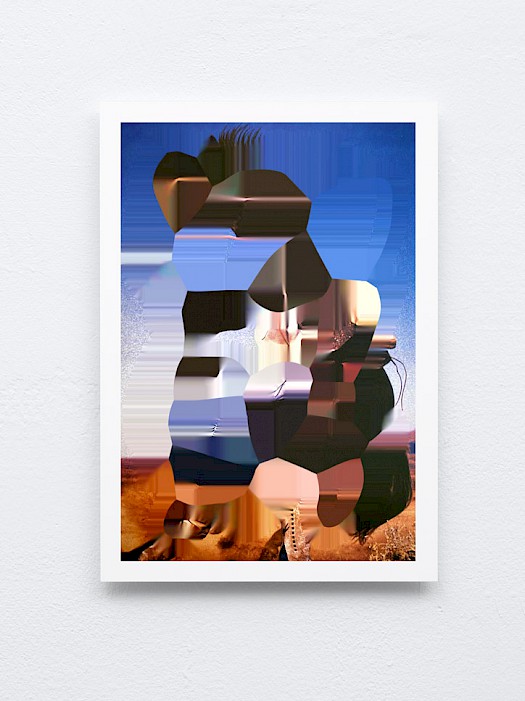

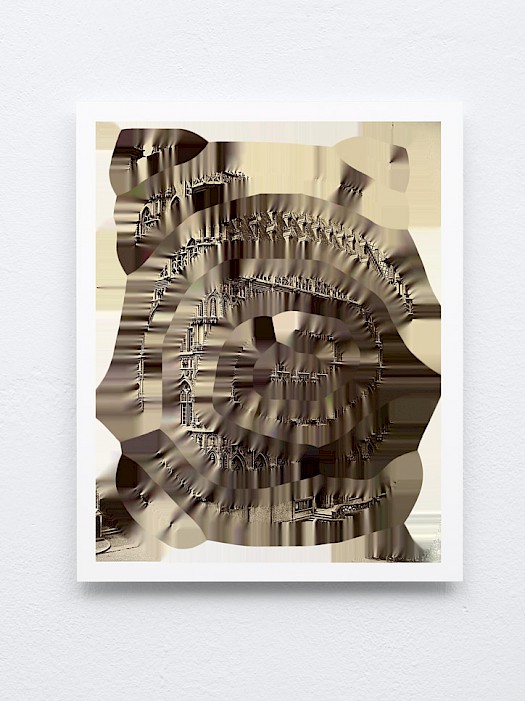

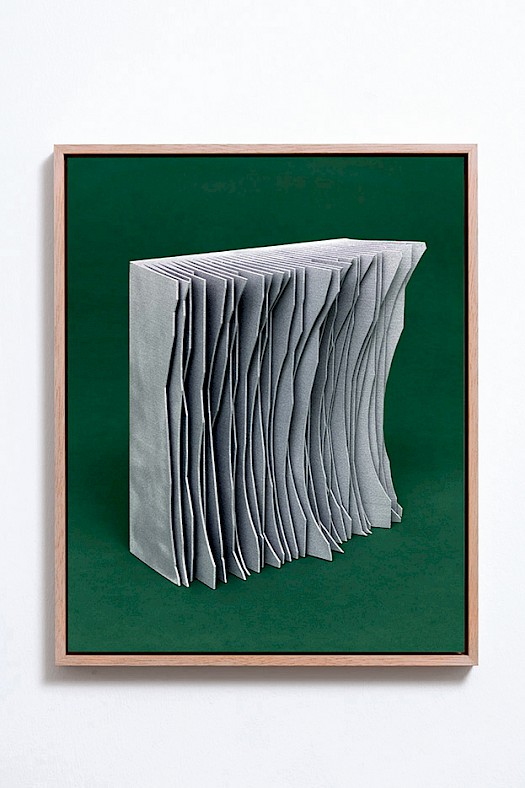

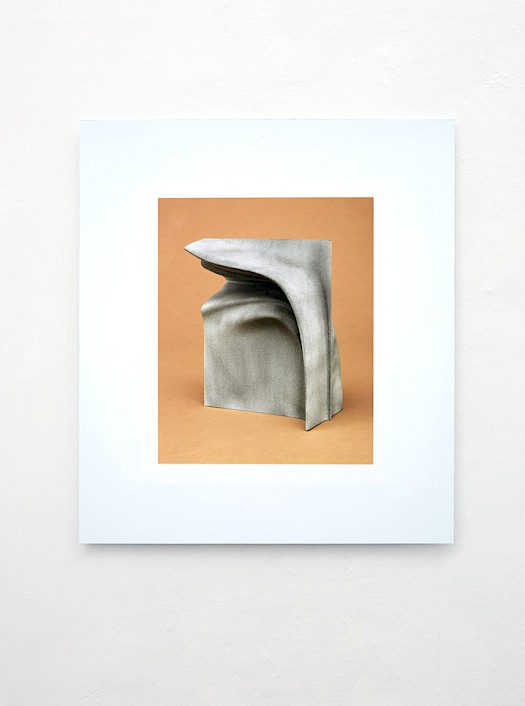

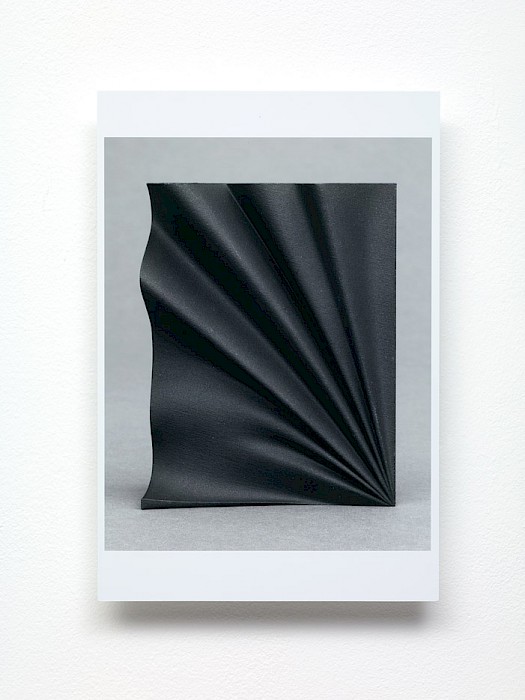

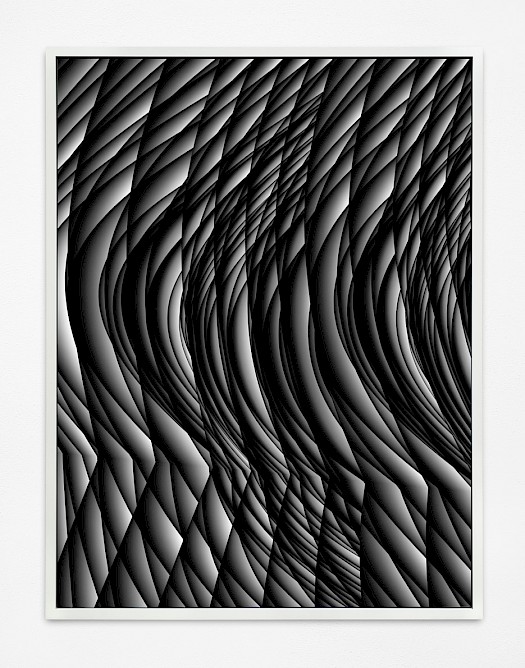

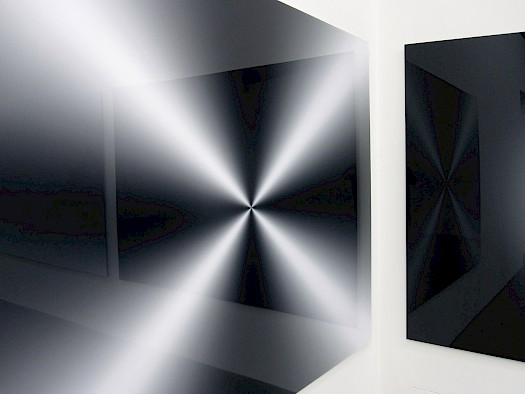

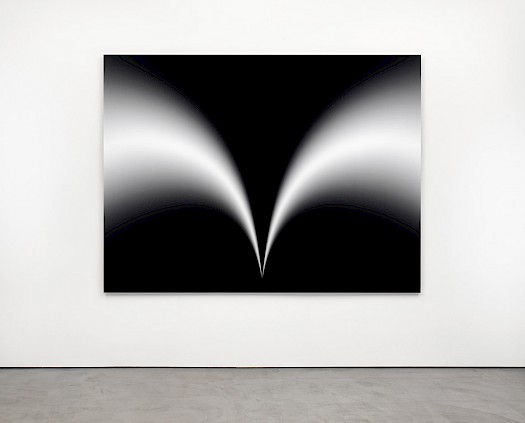

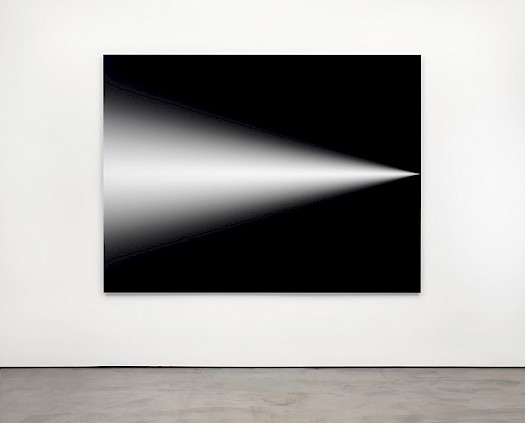

„Trust in those who supposedly know - MURRAY; DONDIE; REBECCA”: Michael Reisch's photography-based works are created in multi-layered, generative work processes that are interrelated and have been continuously building on each other in different "generations" since 2010. The group of works "Trust in those who supposedly know - MURRAY, DONDIE, REBECCA" from 2023/2024 is the latest generation and created with generative AI. Among other things, it addresses contemporary post-truth and ideologization tendencies against the backdrop of current AI technologies, where images and texts can be transformed into anything imaginable regardless of facts. Technically speaking, Reisch has created various abstract-concrete forms, objects and images in previous generations through numerous analog-digital transformation processes (including image editing software, 3D software, 3D printing and digital photography). These now serve as inputs for his further work processes with current AI tools. Reisch feeds digital photos of his free of meaning, abstract form frameworks into diffusion models for image synthesis (including image-to-image and image-to-video tools). They are influenced with specific words and sentences, so-called "prompts", the words merge with the photos fed in and generate new image material. For example, prompts such as " ... 1920's war-memorial, socialistic realism, ..." are used, transforming or morphing/merging/re-mixing the 3D-printed abstract shapes into monumental, historical-futuristic memorials. In this way, Reisch generates various clusters of meaning that associate strongly ideologically charged contexts. The same abstract initial form is inscribed like a kind of stamp in all AI-generated image results (the digital initial form can also be recognized in every start frame of the video loops). Reisch also created the title "Trust in those who supposedly know - MURRAY, DONDIE, REBECCA" using generative AI; scientific texts on the post-truth movement were fed into a GPT-2 AI model that was trained with film scripts. In this way, Reisch generated fictional scripts based on scientifically sound criticism (GPT-2 = still often error-prone predecessor version of Chat-GPT). The text parts generated by GPT-2 were subjectively selected and reassembled (also in other audio works).

deutsch: „MURRAY; DONDIE; REBECCA - trust in those who supposedly know”, Arbeitsprozess, 5-2024

„Trust in those who supposedly know - MURRAY; DONDIE; REBECCA”: Michael Reisch‘s fotografiebasierte Arbeiten entstehen in vielschichtigen, generativen Arbeitsprozessen, die zusammenhängen und in verschiedenen „Generationen“ seit 2010 fortlaufend aufeinander aufbauen. Die Werkgruppe „Trust in those who supposedly know – MURRAY, DONDIE, REBECCA” aus den Jahren 2023/2024 ist die neueste Generation und mit generativer KI erstellt. Sie thematisiert u.a. zeitgenössische Post-Truth- und Ideologisierungs-Tendenzen vor dem Hintergrund aktueller KI-Technologien, wo Bilder und Texte faktenunabhängig in alles Erdenkliche verwandelt werden können. Technisch gesehen hat Reisch in vorherigen Generationen durch zahlreiche analog-digitale Transformationsprozesse (u.a. mit Bildbearbeitungssoftware, 3D-Software, 3D-Druck und digitaler Fotografie ) verschiedene abstrakt-konkrete Formen, Objekte und Bilder erzeugt. Diese dienen nun als Inputs für seine weiteren Arbeitsprozesse mit aktuellen KI-Tools. Reisch speist digitale Fotos seiner bedeutungsfreien, abstrakten Form-Gerüste in Diffusionsmodelle zur Bildsynthese ein (u.a. Image-to-Image-, Image-to-Video-Tools). Sie werden mit gezielten Worten und Sätzen, sog. „Prompts“ beeinflusst, die Worte verschmelzen mit den eingespeisten Fotos und generieren neues Bildmaterial. Beispielsweise werden Prompts wie „ ... 1920’s war-memorial, socialistic realism, ...“ eingesetzt, die die 3D-gedruckten abstrakten Gebilden in monumentale, historisch-futuristische Denkmäler verwandeln, bzw. morphen/mergen/re-mixen. Reisch generiert auf diese Weise verschiedene Bedeutungscluster, die ideologisch stark aufgeladene Zusammenhänge assoziieren. Die immer gleiche abstrakte Ausgangsform schreibt sich dabei wie eine Art Prägestempel in alle KI-generierten Bildergebnisse ein (auch in jedem Startframe der Videoloops ist die digitale Ausgangsform zu erkennen). Den Titel „Trust in those who supposedly know – MURRAY, DONDIE, REBECCA” hat Reisch ebenfalls mit generativer KI erstellt, wissenschaftliche Texte zur Post-Truth-Bewegung wurden in ein GPT-2-KI-Modell eingespeist, das mit Film-Drehbüchern trainiert wurde. Reisch hat auf diese Weise fiktionale Skripte auf Basis von wissenschaftlich fundierter Kritik generiert (GPT-2 = noch häufig fehlerbehaftete Vorläufer-Version von Chat-GPT). Die von GPT-2 generierten Textteile wurden subjektiv ausgewählt und (auch in weiteren Audio-Arbeiten) neu zusammengesetzt.

Ohne Titel (Untitled)_AI, 2021, Fotomuseum Winterthur, "How to win at Photography", 5.6.2021-10.10.2021

readyreadymade, Neuer Kunstverein Aschaffenburg, 26.9.-21.11.2021

Text deutsch + english: iPhone-series, Roland Barthes_AI, 18/, 2020, currently on view at Falko Alexander Galerie, Cologne, 21.5.-20.6.2021

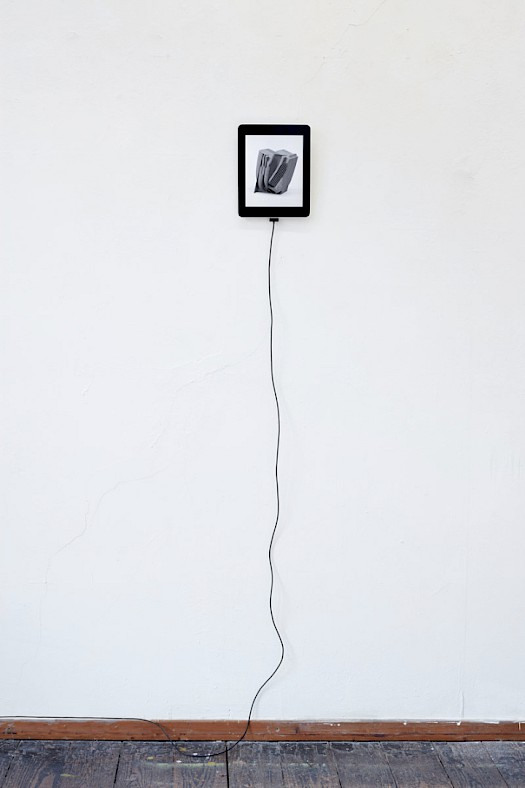

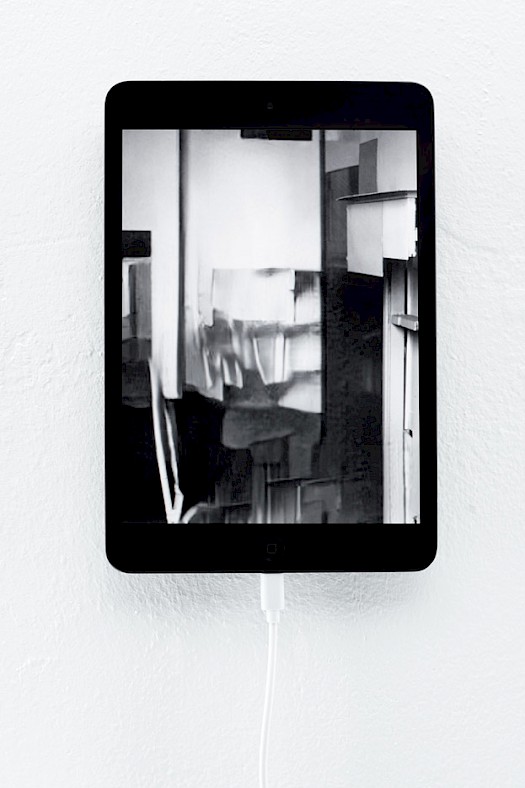

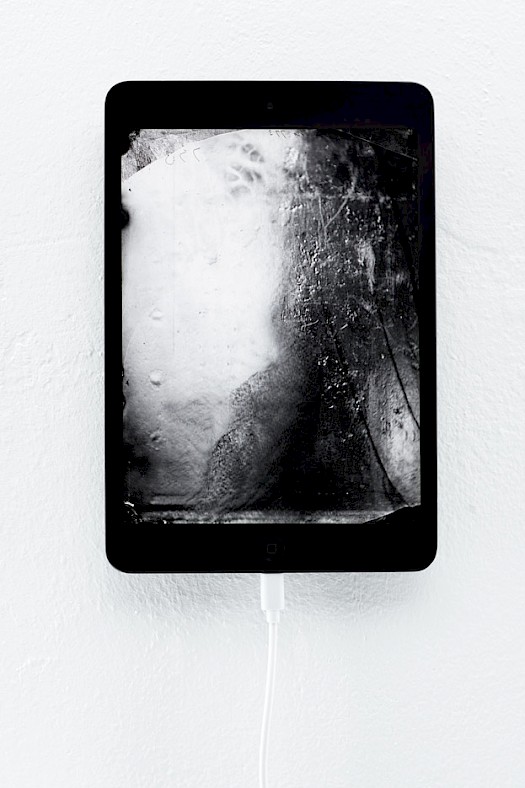

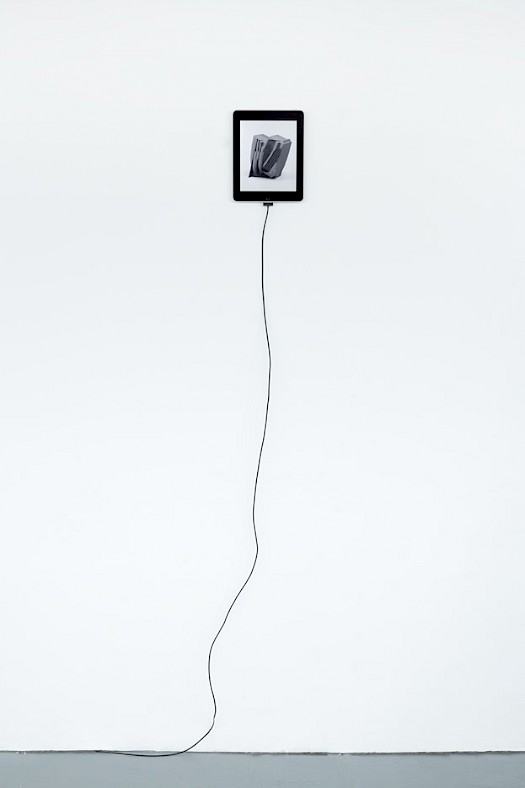

English: For the Roland Barthes_AI series, I "photographed" images from Roland Barthes' famous 1980 book "Camera Lucida" with the iPhone, i.e. I either worked with digital images of the original photographs on the internet, or purchased high-resolution scans of the original photographs, or "photographed" images from the book (from 1980) with the iPhone and thus digitised them myself. I then processed the digitised images with a simple consumer AI app available on the market. The app recognises depicted people by image recognition and retouches them automatically from the image, which only requires a single click. The resulting images are minted by me (tokenised as NFTs), loaded onto a tablet and shown on the screen.

About: iPhone-series

The smartphone has become the accepted camera model, algorithms and AI have transformed "photography" into "computational photography". These new "photographs" are no longer primarily taken, but computed in large parts. In addition, there are new digital tools, such as 3D scanning, photogrammetry and augmented reality, which are now available as apps for consumer photography and which considerably expand the possibilities of "photography".

With a view to current developments, in 2020/21 I created a series of "photographic" works with my smartphone. I work with historical photographs that have a personal, biographical meaning for me, that are, for example, favourite images from analogue times and are representative of a documentary-depictive tradition of photography. I am particularly interested in the extent to which computational photography, smartphones, artificial intelligence and blockchain technology change, expand or overwrite historical photography in the sense of Roland Barthes or Stephen Shore and the models of understanding that go with it.

A necessary prerequisite for my work process is the entry of the original, exclusively analogue source images of the 19th and 20th centuries into the digital field. I have partly worked with digital images of the original photographs on the internet, partly purchased high-resolution scans of the original photographs, i.e. worked with existing digitalisations, or "photographed" images in my photo book collection with the iPhone and thus digitalised them myself. From this point on, the work process runs seamlessly with the iPhone in the digital field. I use consumer software, simple apps available in the app store, which work with artificial intelligence in various ways.

I deliberately start at the point where new technology becomes widely available at the user level and becomes mainstream. My editing steps each consist of one or very few clicks. In some cases the app works with program-bots, i.e. the app also performs computing operations on its external computers and imperceptibly for the user, the image results are streamed back to the iPhone.

The finished files are "minted" by me, provided as NFTs with a certificate on the blockchain and shown on screens/tablets, some are printed as fine art prints and transferred back into analogue space.

Besides the new everydayness and general availability of the tools, what interests me most is their highly standardised character. The apps are designed for mass use and leave very little (sometimes no) room for decision-making in their use. Algorithms and AI take over almost all image decisions in the application, there are no or only very minimal adjustment possibilities in the apps used. It seemed interesting to me to what extent an artistic work is possible under these highly restricted conditions (also referring to Vilèm Flusser, who names working against the program of the apparatus as a possible creative act), and how the interaction with the programs can be shaped in this respect. I therefore refer to the works as "digital détournements". My particular focus is on delegating image decisions to AI, how does human decision-making relate to machine image recognition and to machine decision-making in this framework? (Michael Reisch, 2021)

Deutsch: Für die Serie "iPhone-series: Roland Barthes_AI" habe ich Abbildungen aus Roland Barthes berühmtem Buch „Die helle Kammer“ aus dem Jahr 1980 mit dem iPhone „fotografiert“, d.h. ich habe fallweise mit digitalen Abbildungen der originalen Fotografien im Internet gearbeitet, oder High-Resolution-Scans der originalen Fotografien angekauft, oder Abbildungen aus dem Buch mit dem iPhone „fotografiert“ und so selbst digitalisiert. Anschließend habe ich die digitalisierten Abbildungen mit einer einfachen, im Handel erhältlichen Consumer-KI-App bearbeitet. Die App erkennt durch Bilderkennung abgebildete Personen und retuschiert diese automatisch aus dem Bild, wofür nur ein einziger Klick erforderlich ist. Die so entstandenen Bilder werden von mir gemintet (als NFTs tokenisiert), auf ein Tablet geladen und auf dem Screen gezeigt. (Michael Reisch, 2021)

Über: iPhone-series

Das Smartphone hat sich als Kameramodell durchgesetzt, Algorithmen und KI haben „Photography“ zu "Computational Photography" transformiert. Diese neuen „Fotografien“ werden nicht mehr in erster Linie aufgenommen, sondern in großen Anteilen errechnet. Hinzu kommen neue digitale Tools, wie z.B. 3D-Scanning, Photogrammetrie, oder Augmented Reality, die für die Gebrauchsfotografie als Apps auf Consumer*innen-Level inzwischen leicht verfügbar sind, und die Möglichkeiten der „Fotografie“ erheblich erweitern.

2020/21 habe ich mit Blick auf die aktuellen Entwicklungen eine Reihe von „fotografischen“ Arbeiten mit meinem Smartphone erstellt. Dabei arbeite ich mit historischen Fotografien, die für mich eine persönliche, biographische Bedeutung haben, die z.B. Lieblingsbilder aus analogen Zeiten sind und stellvertretend für eine dokumentarisch-abbildende Tradition der Fotografie stehen. Insbesondere interessiert mich, inwieweit Computational Photography, Smartphone, Künstliche Intelligenz und Blockchain-Technologie die historische Fotografie im Sinne Roland Barthes oder Stephen Shores und die damit einhergehenden Verständnismodelle verändern, erweitern oder überschreiben.

Notwendige Voraussetzung für meinen Arbeitsprozess ist der Eintritt der im Original ausschließlich analogen Ausgangsbilder des 19. und 20.Jh. ins digitale Feld. Ich habe teilweise mit digitalen Abbildungen der originalen Fotografien im Internet gearbeitet, teilweise High-Resolution-Scans der originalen Fotografien angekauft, also mit bestehenden Digitalisierungen gearbeitet, oder Abbildungen in meiner Fotobuchsammlung mit dem iPhone „fotografiert“ und so selbst digitalisiert. Ab dieser Stelle läuft der Arbeitsprozess nahtlos (seamless) mit dem iPhone im Digitalen Feld ab. Ich verwende dazu Consumersoftware, einfache, im App-store verfügbare Apps, die in verschiedener Weise mit Künstlicher Intelligenz arbeiten.

Ich setze dabei bewusst an dem Punkt an, wo neue Technologie auf breiter Basis auf User-Level verfügbar wird und sich im allgemeinen Gebrauch durchsetzt. Meine Bearbeitungsschritte bestehen jeweils aus einem bzw. sehr wenigen Klicks. In einigen Fällen funktioniert die App mit program-bots, d.h. die App führt auch Rechenoperationen auf ihren externen Rechnern und für die User*innen unmerklich durch, die Bildergebnisse werden auf das iPhone zurückgestreamt.

Die fertig-bearbeiteten Dateien werden von mir „gemintet“ und als NFTs mit einem Zertifikat auf der Blockchain versehen und auf Screens/Tablets gezeigt, einige werden als Fine-Art-Prints ausgedruckt und wieder in analogen Raum zurücküberführt.

Mich interessiert neben der neuen Alltäglichkeit und allgemeinen Verfügbarkeit der Tools vor allem ihr stark standardisierter Charakter. Die Apps sind auf den Massengebrauch ausgelegt und lassen sehr wenig (manchmal keinen) Entscheidungsspielraum im Gebrauch zu, Algorithmen und KI übernehmen in der Anwendung fast alle Bildentscheidungen, es gibt keine, oder nur sehr minimale Justiermöglichkeiten in den verwendeten Apps. Mir schien interessant, inwieweit eine künstlerische Arbeit unter diesen höchst eingeschränkten Voraussetzungen möglich ist (auch bezugnehmend auf Vilèm Flusser, der die Arbeit gegen das Programm der Apparate als möglichen kreativen Akt benennt), und wie sich in dieser Hinsicht die Interaktion mit den Programme gestalten lässt. Ich bezeichne die Arbeiten daher auch als „digitale Détournements“. Mein besonderes Augenmerk liegt auf dem Delegieren von Bildentscheidungen an KI, wie verhält sich in diesem Rahmen menschliche Entscheidungsfindung zu maschineller Bilderkennung und zu maschineller Entscheidungsfindung? (Michael Reisch, 2021)

Text deutsch + english: iPhone-series, 19/, 2020, solo-exhibition Falko Alexander Galerie, Cologne, 21.5.-20.6.2021

English: For the series "after/d'après Stephen Shore, Merced River", etc., I edited some of my favourite photos from analogue times, which I understand to be representative of a documentary-depictive conception of photography, with the iPhone. To do this, I used a simple AI image editing app available in the app store and used it against its intended purpose, as a digital détournement. These images are printed on fine art paper as Archival Pigment Prints, mounted and presented in analogue.

About: iPhone-series:

The smartphone has become the accepted camera model, algorithms and AI have transformed "photography" into "computational photography". These new "photographs" are no longer primarily taken, but computed in large parts. In addition, there are new digital tools, such as 3D scanning, photogrammetry and augmented reality, which are now available as apps for consumer photography and which considerably expand the possibilities of "photography".

With a view to current developments, in 2020/21 I created a series of "photographic" works with my smartphone. I work with historical photographs that have a personal, biographical meaning for me, that are, for example, favourite images from analogue times and are representative of a documentary-depictive tradition of photography. I am particularly interested in the extent to which computational photography, smartphones, artificial intelligence and blockchain technology change, expand or overwrite historical photography in the sense of Roland Barthes or Stephen Shore and the models of understanding that go with it.

A necessary prerequisite for my work process is the entry of the original, exclusively analogue source images of the 19th and 20th centuries into the digital field. I have partly worked with digital images of the original photographs on the internet, partly purchased high-resolution scans of the original photographs, i.e. worked with existing digitalisations, or "photographed" images in my photo book collection with the iPhone and thus digitalised them myself. From this point on, the work process runs seamlessly with the iPhone in the digital field. I use consumer software, simple apps available in the app store, which work with artificial intelligence in various ways.

I deliberately start at the point where new technology becomes widely available at the user level and becomes mainstream. My editing steps each consist of one or very few clicks. In some cases the app works with program-bots, i.e. the app also performs computing operations on its external computers and imperceptibly for the user, the image results are streamed back to the iPhone.

The finished files are "minted" by me, provided as NFTs with a certificate on the blockchain and shown on screens/tablets, some are printed as fine art prints and transferred back into analogue space.

Besides the new everydayness and general availability of the tools, what interests me most is their highly standardised character. The apps are designed for mass use and leave very little (sometimes no) room for decision-making in their use. Algorithms and AI take over almost all image decisions in the application, there are no or only very minimal adjustment possibilities in the apps used. It seemed interesting to me to what extent an artistic work is possible under these highly restricted conditions (also referring to Vilèm Flusser, who names working against the program of the apparatus as a possible creative act), and how the interaction with the programs can be shaped in this respect. I therefore refer to the works as "digital détournements". My particular focus is on delegating image decisions to AI, how does human decision-making relate to machine image recognition and to machine decision-making in this framework? (Michael Reisch, 2021)

Deutsch: Für die Serie "iPhone-series: after/d’après Stephen Shore, Merced River“, etc. habe ich einige meiner Lieblingsfotos aus analogen Zeiten, die ich stellvertretend für eine dokumentarisch-abbildende Auffassung von Fotografie verstehe, mit dem iPhone bearbeitet. Hierzu habe ich eine einfache, im App-Store erhältliche KI-Bildbearbeitungs-Apps verwendet und diese gegen den für sie vorgesehenen Einsatzzweck eingesetzt, als digitales Détournement. Diese Bilder sind auf Fine-Art-Papier als Archival Pigment Prints ausgedruckt, aufgezogen und werden analog präsentiert. (Michael Reisch, 2021)

Über: iPhone-series

Das Smartphone hat sich als Kameramodell durchgesetzt, Algorithmen und KI haben „Photography“ zu "Computational Photography" transformiert. Diese neuen „Fotografien“ werden nicht mehr in erster Linie aufgenommen, sondern in großen Anteilen errechnet. Hinzu kommen neue digitale Tools, wie z.B. 3D-Scanning, Photogrammetrie, oder Augmented Reality, die für die Gebrauchsfotografie als Apps auf Consumer*innen-Level inzwischen leicht verfügbar sind, und die Möglichkeiten der „Fotografie“ erheblich erweitern.

2020/21 habe ich mit Blick auf die aktuellen Entwicklungen eine Reihe von „fotografischen“ Arbeiten mit meinem Smartphone erstellt. Dabei arbeite ich mit historischen Fotografien, die für mich eine persönliche, biographische Bedeutung haben, die z.B. Lieblingsbilder aus analogen Zeiten sind und stellvertretend für eine dokumentarisch-abbildende Tradition der Fotografie stehen. Insbesondere interessiert mich, inwieweit Computational Photography, Smartphone, Künstliche Intelligenz und Blockchain-Technologie die historische Fotografie im Sinne Roland Barthes oder Stephen Shores und die damit einhergehenden Verständnismodelle verändern, erweitern oder überschreiben.

Notwendige Voraussetzung für meinen Arbeitsprozess ist der Eintritt der im Original ausschließlich analogen Ausgangsbilder des 19. und 20.Jh. ins digitale Feld. Ich habe teilweise mit digitalen Abbildungen der originalen Fotografien im Internet gearbeitet, teilweise High-Resolution-Scans der originalen Fotografien angekauft, also mit bestehenden Digitalisierungen gearbeitet, oder Abbildungen in meiner Fotobuchsammlung mit dem iPhone „fotografiert“ und so selbst digitalisiert. Ab dieser Stelle läuft der Arbeitsprozess nahtlos (seamless) mit dem iPhone im Digitalen Feld ab. Ich verwende dazu Consumersoftware, einfache, im App-store verfügbare Apps, die in verschiedener Weise mit Künstlicher Intelligenz arbeiten.

Ich setze dabei bewusst an dem Punkt an, wo neue Technologie auf breiter Basis auf User-Level verfügbar wird und sich im allgemeinen Gebrauch durchsetzt. Meine Bearbeitungsschritte bestehen jeweils aus einem bzw. sehr wenigen Klicks. In einigen Fällen funktioniert die App mit program-bots, d.h. die App führt auch Rechenoperationen auf ihren externen Rechnern und für die User*innen unmerklich durch, die Bildergebnisse werden auf das iPhone zurückgestreamt.

Die fertig-bearbeiteten Dateien werden von mir „gemintet“ und als NFTs mit einem Zertifikat auf der Blockchain versehen und auf Screens/Tablets gezeigt, einige werden als Fine-Art-Prints ausgedruckt und wieder in analogen Raum zurücküberführt.

Mich interessiert neben der neuen Alltäglichkeit und allgemeinen Verfügbarkeit der Tools vor allem ihr stark standardisierter Charakter. Die Apps sind auf den Massengebrauch ausgelegt und lassen sehr wenig (manchmal keinen) Entscheidungsspielraum im Gebrauch zu, Algorithmen und KI übernehmen in der Anwendung fast alle Bildentscheidungen, es gibt keine, oder nur sehr minimale Justiermöglichkeiten in den verwendeten Apps. Mir schien interessant, inwieweit eine künstlerische Arbeit unter diesen höchst eingeschränkten Voraussetzungen möglich ist (auch bezugnehmend auf Vilèm Flusser, der die Arbeit gegen das Programm der Apparate als möglichen kreativen Akt benennt), und wie sich in dieser Hinsicht die Interaktion mit den Programme gestalten lässt. Ich bezeichne die Arbeiten daher auch als „digitale Détournements“. Mein besonderes Augenmerk liegt auf dem Delegieren von Bildentscheidungen an KI, wie verhält sich in diesem Rahmen menschliche Entscheidungsfindung zu maschineller Bilderkennung und zu maschineller Entscheidungsfindung? (Michael Reisch, 2021)

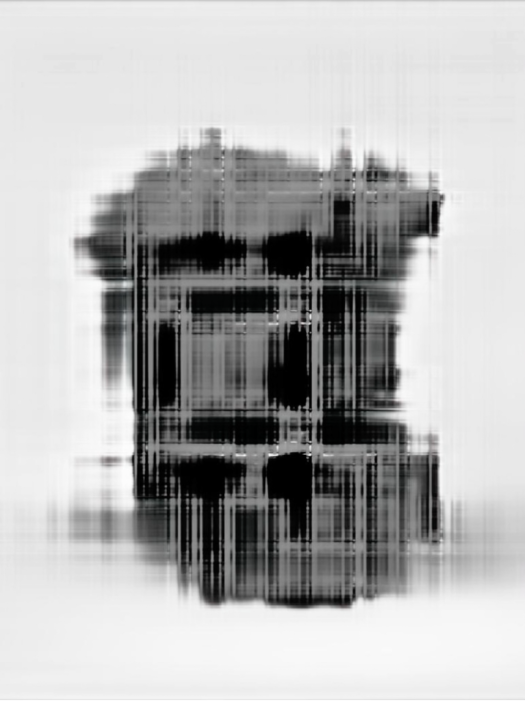

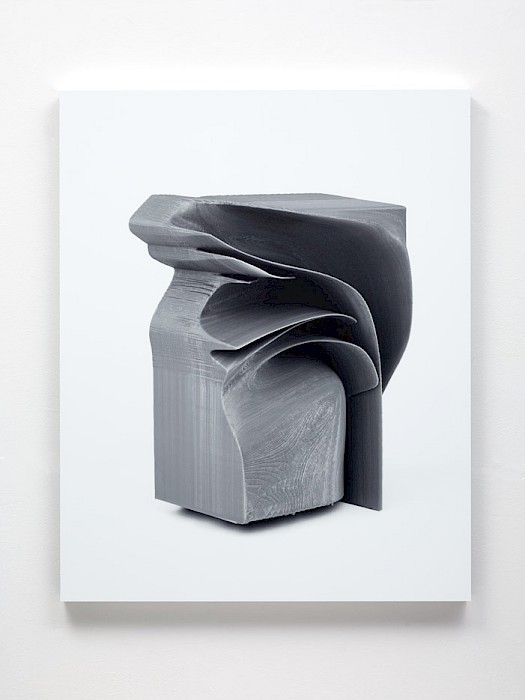

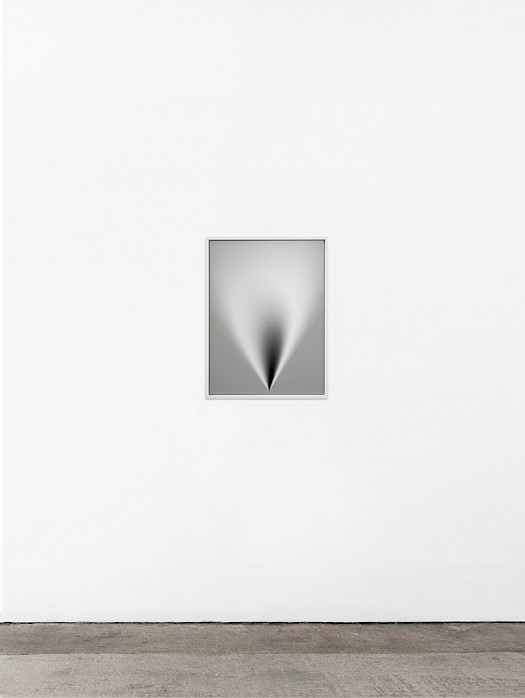

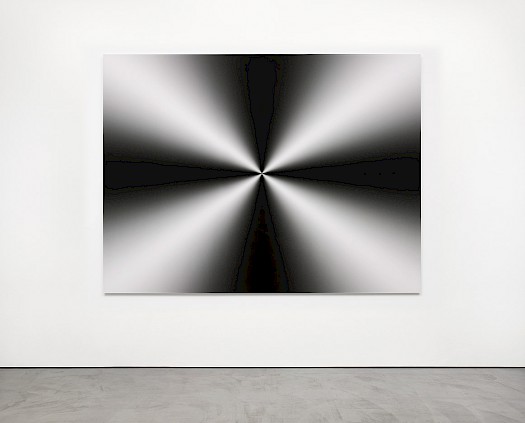

About: Ohne Titel (Untitled), 17/, — something and nothing, working-process

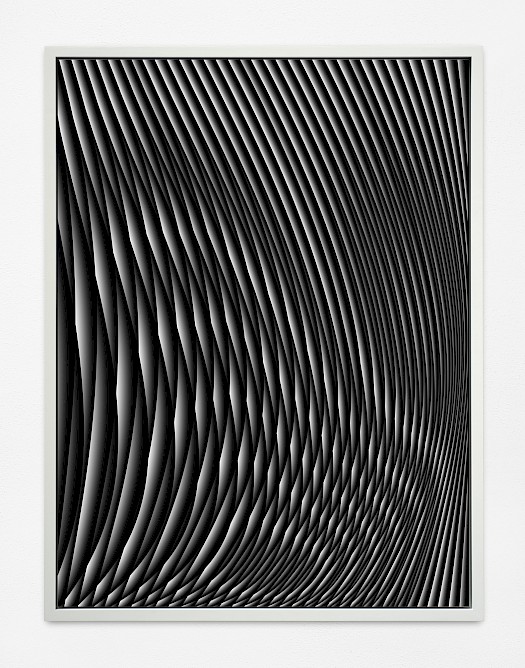

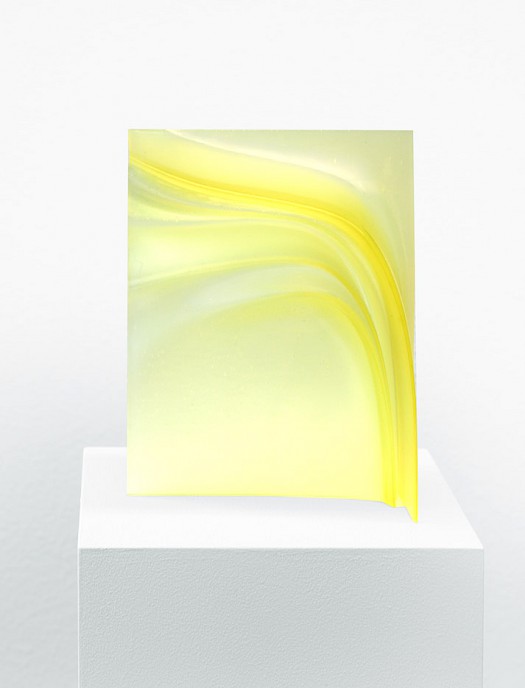

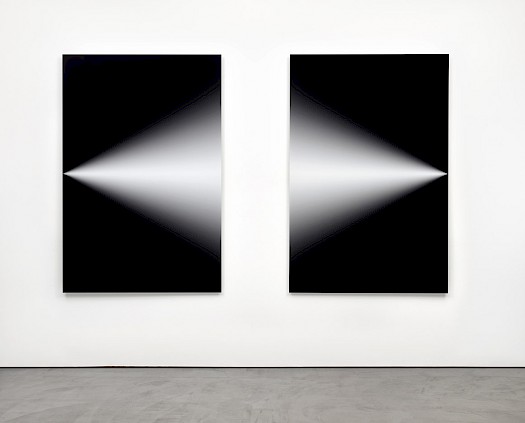

In a camera-less process, I start with generating black and white lines and curves from within a chosen computer software programme (a common photo-editing-software). I provoke optical illusions and interferences to occur, so that my images become recognisable as “things”, as if something was there – with a layered, stratified or folded character, for example. These generated optical illusions, the “things” meant to be seen, are then materialised – i.e. I imagine how these might look as real, physically existing objects, and recreate them using computer-aided design programs as virtual 3D-objects. I store them as data-files and afterwards 3D-print them as “real“, material objects (in a range of 3D-printable materials).

In a next working step the generated and materialised objects/entities are photographed in a photo studio, in a documentary sense. I understand the final images as photographs of “motifs/subjects”, that in some way do exist – since they are 3D-printed and exist in material form – and that on the other hand do not exist – since they are based on optical illusion and have no starting point in the “real world”.

Instead of starting from the material world, from existing facts and turning it into information and data – like traditional photography mostly does – I reverse this conventional direction of “photography”. Starting from the operational substructure of digital photography, its own tools, I turn immaterial data and algorithms to factual and thus touchable and “photographable” objects, to again transform these objects into data (photos) and images (and so on in next working steps). The concept of recording as constitutive for photography for me functions in both directions, the photos record the 3D-printed objects, but also I understand the printed 3D-objects as “material photos”, as material recordings of the images.

What interests me here, amongst others, are the concepts of “something” and “nothing”, especially on the backdrop of photography and the digital realm. When do we (with our human eyes) consider something to be there, and under what circumstances? In a traditional sense, above all photography was meant to document and approve the existence of a subject matter, of “something”. Which role does the medium of photography play under digital conditions, when “existence”, “something being there”, can be generated from “nothing”, and when this “something” is at any time reversible and transformable (if it appears as code or as a representation of code, for example as a digitally constituted image)? What about the transformations from material to image to material in this regard?

I would like to add, that all working steps during the process are interactions between the possibilities and automatic qualities of the apparatus, of the machinic systems and algorithms, and my–human–subjective, aesthetic decisions. I am steering the machine’s and algorithm’s “proposals”, feeding the so received results back again to the apparatus, the apparatus sends its updated “proposals” back to me, and so on, vice-versa.

The entire process of creation is generative and evolutionary, different generations of images and of “objects/entities” develop out of each other, creating new generations. For example, some of my photos and objects are 3D-scanned and appear transformed as videos or as prints. Also I photographed all my 3D-printed objects, and used them as dataset to train a GAN (AI), which then generates pictures of new objects/entities, that are again 3D-printed, again photographed, and so on.

Once derived from a primary photo-editing tool, the generations are growing into an increasingly complex system of interrelated “appearances”, through superposition and intertwining of recordings and renderings, of generative and documentary working methods, of “traditionally photographic” and the new, digitally constituted tools.

(Michael Reisch, 2021)

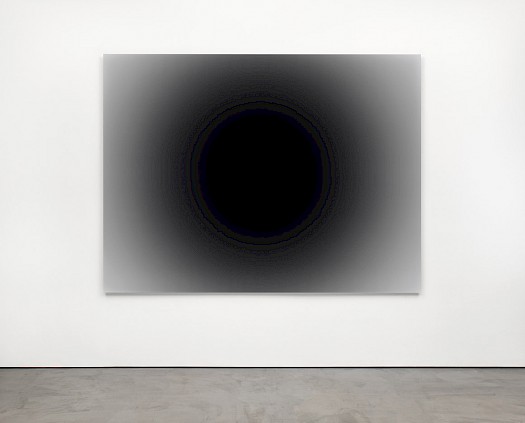

new works 15/, 2014-2016+: I digitally generate interferences in a conventional 2D photo-editing program until an impression of „something being there“ occurs. This „claim of objecthood“ is due to an optical illusion and based on the digital operative substructure, the algorithm only, no depictive photographic action or digital 3D-modeling involved.

Present Progressive, Exhibition Felix Ringel Galerie, Düsseldorf, February/March 2018

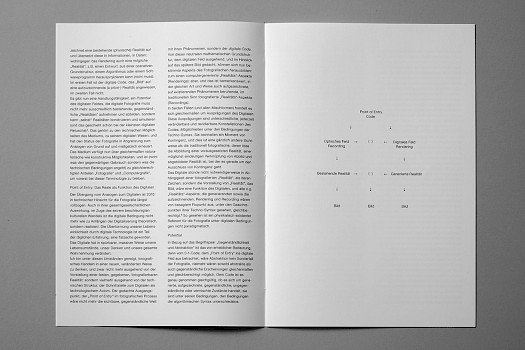

Text: Realität als Funktion des Codes - Gegenständlichkeit und Abstraktion für die Fotografie unter digitalen Bedingungen/ Reality as a Function of Code - Photographic Representation and Abstraction in the Digital Realm, Michael Reisch, April 2016

Installation Views, Solo Exhibition, "Selected Works 2008-2013", Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Germany, 2013

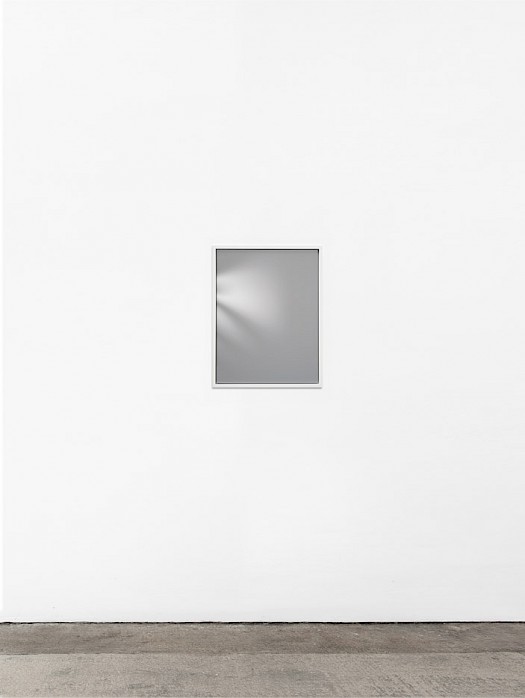

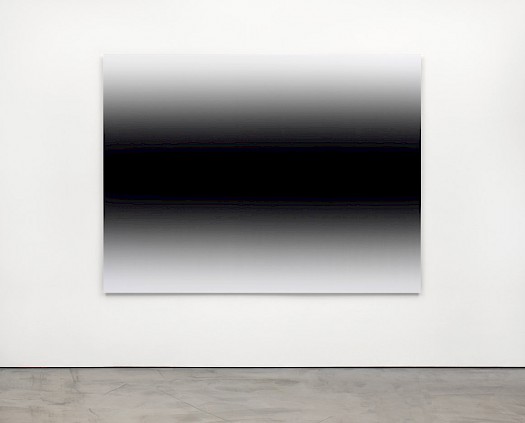

working group 8/, 2010 - 2013: Developed from a photographic context, working group 8/ is created cameraless without any reference in the physical, „photographable“ world. Using a common tool of a conventional 2D photo-editing program I digitally generate gradients, “depicting” the programs tool.